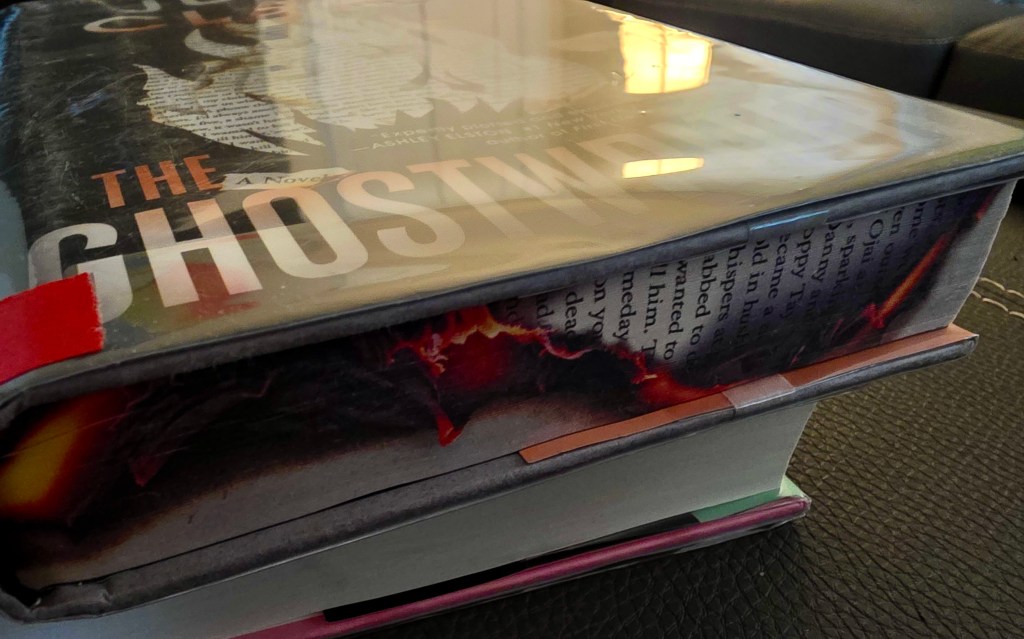

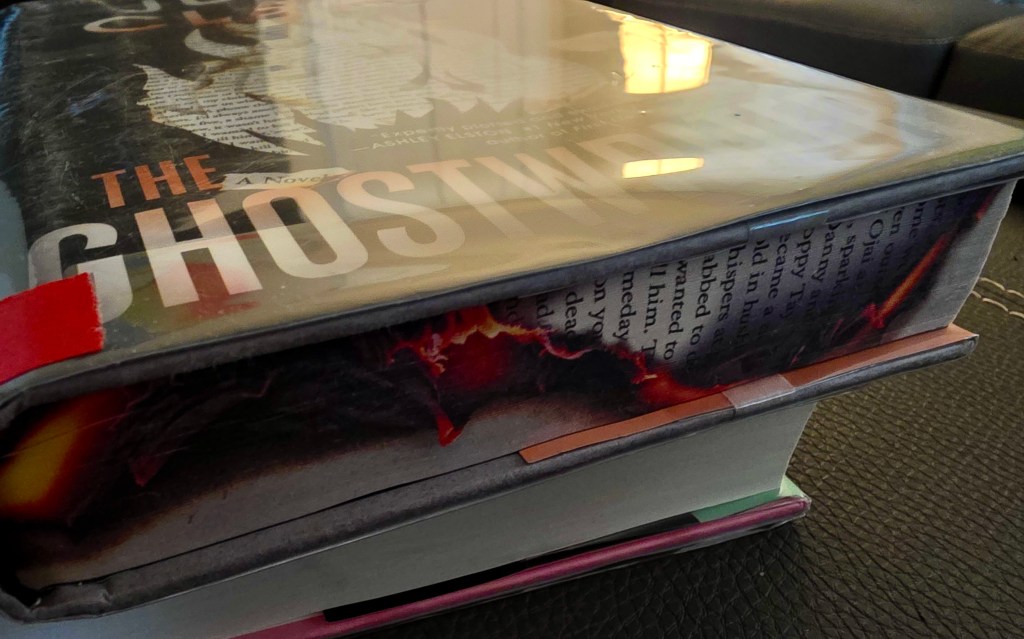

Love the printing on the book block’s trimmed edges. Grabbed my eye from the new-book shelves at the library. It’s “The Ghostwriter” by Julie Clark.

Writer. Editor. Photographer.

Love the printing on the book block’s trimmed edges. Grabbed my eye from the new-book shelves at the library. It’s “The Ghostwriter” by Julie Clark.

This ranks as one of the most fun and fascinating conversations I’ve had this year about the power of the printed newspaper and media literacy.

Meet TikTok’s “Print Princess,” Kelsey Russell, who leverages the platform to introduce her audience to news of the day; how to be critical about what they read; and how print can give us a break from screen time, as well as help us more meaningfully consider and retain information.

https://www.editorandpublisher.com/stories/meet-the-print-princess-tiktok-personality-kelsey-russell-uses-social-media-to-spark-critical,250283

When I was growing up, libraries seemed this quiet, unassuming certainty in everyday life. They were well-funded, accessible to everyone in the community, no matter why nor when you needed them. I saw librarians as all-knowing beings, who could find even the most obscure title on the stacks, without so much as a glance at a card catalog.

I worked for a while at my university library, in the periodical section. When students came in looking for references, I’d pull out newspapers and magazines from the bowels of the back or help them learn to use the microfiche machines — high-tech back then.

It may have been my paternal grandmother and her mother (Ida Locke, a librarian seen here) who encouraged my early reading.

Great-grandmother Locke lived with my grandparents, and I have fond memories of her seated on their sofa, a stack of books always present on the end table beside her. An insatiable reader, she could sail through a book in a single afternoon. She was a quiet, tiny mouse of a woman, always dressed for going out, even when there was no place to go. I can’t remember her voice, because she rarely offered even a hint of a smile nor a string of spoken words. But when I’d visit, she’d pat the sofa next to her, inviting me to sit and tell her what I was reading that week. Born to a German community in rural West Virginia, books were her way to rise above, to escape, to aspire — to work and have autonomy as a woman of that era.

Books didn’t change her nature — who she was or how she conducted her simple, frugal life — but they did broaden her perspective and informed her understanding of the world outside of her own.

I think about her a lot lately, as libraries are under attack from so many directions. Funding is imperiled. Politics has landed on their doorsteps. Shamefully, surreally, book bans — patently anti-liberty and anti-intellectual — are part of our national discourse. Librarians themselves are harassed and forced out of their jobs by politically motivated and dark money-funded mobs. Can democracy survive under these circumstances, I wonder? It feels symbolic of how we’ve lost our way.

This headline may not be entirely true, and yet, it was in this pre-Middle School era of my life when I first began to fully “understand the value of a dollar.”

I find that’s a popular phrase passed down through generations, an invaluable life lesson or a rite of passage. For two sixth-grade classes in the 1970s, their introduction to commerce and capitalism began that week.

That was the year that the number of students had outgrown the school, and some lucky contractor got the local school system bid for providing pop-up classrooms made out of stitched-together double-wide trailers. Two sixth-grade classes shared the one we’d been sentenced to, with a sliding partition between the two groups, each with its own teacher.

The partition was an insufficient barrier that mostly rendered us distracted by what was happening with the kids on the other side. When they laughed, our heads swiveled. When we acted up, they’d go silent and giggle as they listened to our punishment being levied. One teacher would have to raise her voice to keep the attention of her class whenever the sounds of the other teacher seemed more interesting.

And vice versa, and so it went.

Imagine the delight in our little hearts when one day the partition was folded in on itself, the two classrooms of kids facing off at last. The once competitive teachers joined forces and announced that we were going to learn about running a business and paying bills. They went on to explain that for a period of one week, there would be no traditional classroom lessons and that our trailer would be transformed into a microcosmic town.

Each of us had a role to play in the town. They asked for a show of hands when assigning roles like bankers, retailers, landlords, food purveyors, even insurance carriers.

I was the only one who wanted to run the town’s newspaper.

The town also needed governance, and so a show of hands indicated which of my classmates aspired to political life – managing their day-to-day duties while also running for a handful of offices, including mayor and sheriff.

We spent a day or two planning and building the town. Creative cardboard cutouts became our storefronts. Logos were designed, and signs went up over our storefronts. My classmates got right to work. The banker “handprinted” money and distributed a precisely equal amount of cash to each of the town’s residents, so everyone had a level playing field – a comparatively endearing socialist start to what would end in survival-of-the-fittest capitalistic carnage.

The most popular business, by far, was the town baker, who sold decadent treats to a classroom of kids given the freedom to make their own nutritional and expenditure decisions.

We didn’t speak of food allergies back then.

I got right to work wearing all the hats at the newspaper – a lot like things are today.

I reported and designed the layout. I “printed” the paper on the front office’s mimeograph. Printing is a big cost for actual newspapers, but I’d managed to get the paper and “press” for free. This would be seen as an ethical breach for actual newspapers.

I had to hock the paper, selling single copies to passersby. I sold advertising and wrote ad copy. I had to distribute the paper when it was hot off the press.

And though everyone wanted to read the paper – mostly to see if they were in it – few wanted to buy the paper. It was hard to compete with Mom-baked brownies.

I spent the week walking around the perimeter of the trailer, interviewing my classmates about the health of their businesses or who they liked in the pending election. I wrote trends pieces about how the town’s residents thought the rent was too damned high and how they wanted to be able to spend more of their money on luxury items, like those chocolately brownies. I vaguely remember writing an expose on the insurance carrier in town, who I saw as a huckster selling vapor.

“People give you money, but what do they really get in return,” I grilled him like I was Woodward or Bernstein.

One by one, the small businesses fell, exiling their owners from town, to a corner of the trailer-classroom to watch an episode of “Free to be You and Me” or to throw a sixth-grade temper tantrum, perhaps.

Naturally, the bank endured; it thrived off of the interest. The insurance carrier – who had minimal overhead costs and a contained, safe environment that put odds in his favor – stayed afloat. The baker had fistfuls of colorful cash by week’s end. And the newspaper endured, though I, too, was pretty busted. By the time I’d covered my own costs – rent, insurance, crayons – I didn’t have enough currency for much else.

I’d spent days coveting my classmates’ disposable income and how they frivolously, happily spent it on baked goods and insurance policies.

Somehow, I’d managed to get the news out, but it wasn’t easy, and it wasn’t lucrative.

This headline is not true, and yet, it was in this pre-Middle School era of my life when I first began to fully “understand the value of a dollar.”

I find that’s a popular phrase passed down through generations, an invaluable life lesson or a rite of passage. For two sixth-grade classes in the 1970s, their introduction to commerce and capitalism began that week.

That was the year that the number of students had outgrown the school, and some lucky contractor got the local school system bid for providing pop-up classrooms made out of stitched-together double-wide trailers. Two sixth-grade classes shared the one we’d been sentenced to, with a sliding partition between the two groups, each with its own teacher.

The partition was an insufficient barrier that mostly rendered us distracted by what was happening with the kids on the other side. When they laughed, our heads swiveled. When we acted up, they’d go silent and giggle as they listened to our punishment being levied. One teacher would have to raise her voice to keep the attention of her class whenever the sounds of the other teacher seemed more interesting.

And vice versa, and so it went.

Imagine the delight in our little hearts when one day the partition was folded in on itself, the two classrooms of kids facing off at last. The once competitive teachers joined forces and announced that we were going to learn about “the value of money.” They went on to explain that for a period of one week, there would be no traditional classroom lessons and that our trailer would be transformed into a microcosmic town.

Each of us had a role to play in the town. They asked for a show of hands when assigning roles like bankers, retailers, landlords, food purveyors, even insurance carriers.

I was the only one who wanted to run the town’s newspaper.

The town also needed governance and law, and so a show of hands indicated which of my classmates aspired to political life – managing their day-to-day duties while also running for a handful of offices, including mayor and sheriff.

We spent a day or two planning and building the town. Creative cardboard cutouts became our storefronts. Logos were designed, and signs went up over our storefronts. My classmates got right to work. The banker “handprinted” money and distributed a precisely equal amount of cash to each of the town’s residents, so everyone had a level playing field – a comparatively endearing socialist start to what would end in survival-of-the-fittest capitalistic carnage.

The most popular business, by far, was the town baker, who sold decadent treats to a classroom of kids given the freedom to make their own nutritional and expenditure decisions.

We didn’t speak of food allergies back then.

I got right to work wearing all the hats at the newspaper – a lot like things are today.

I reported and designed the layout. I “printed” the paper on the front office’s mimeograph. Printing is a big cost for actual newspapers, but I’d managed to get the paper and “press” for free. This would be seen as an ethical breach for actual newspapers.

I had to hock the paper, selling single copies to passersby. I sold advertising and wrote ad copy. I had to distribute the paper when it was hot off the press.

And though everyone wanted to read the paper – mostly to see if they were in it – few wanted to buy the paper. It was hard to compete with Mom-baked brownies.

I spent the week walking around the perimeter of the trailer, interviewing my classmates about the health of their businesses or who they liked in the pending election. I wrote trends pieces about how the town’s residents thought the rent was too damned high and how they wanted to be able to spend more of their money on luxury items, like those chocolately brownies. I vaguely remember writing an expose on the insurance carrier in town, who I saw as a huckster selling vapor.

“People give you money, but what do they really get in return,” I grilled him like I was Woodward or Bernstein.

One by one, the small businesses fell, exiling their owners from town, to a corner of the trailer-classroom to watch an episode of “Free to be You and Me” or to throw a sixth-grade temper tantrum, perhaps.

Naturally, the bank endured; it thrived off of the interest. The insurance carrier – who had minimal overhead costs and a contained, safe environment that put odds in his favor – stayed afloat. The baker had fistfuls of colorful cash by week’s end. And the newspaper endured, though I, too, was pretty busted. By the time I’d covered my own costs – rent, insurance, crayons – I didn’t have enough currency for much else.

I’d spent days coveting my classmates’ disposable income and how they frivolously, happily spent it on baked goods and insurance policies.

Somehow, I’d managed to get the news out, but it wasn’t easy, and it wasn’t lucrative.

By Gretchen A. Peck

If newspaper design had a motto, it might be: “Stick to the format. The design and layout is the brand.”

And that remains true today with iconic titles of newspapers rendered in familiar fonts and layouts that are distinctive in their own right. Think of how familiar and distinctive a title like USA Today is when you flip through the pages. The color, the layout, the way the headlines grab your attention—all part of the brand.

Newspaper publishers, by and large, have always understood this. But the notion that printed newspapers’ design should never deviate from the template is being challenged, and it’s because of digital and mobile publishing and the rising cost to paper. Still, that hasn’t stopped publishers from experimenting with their print product.

Read more at Editor & Publisher magazine: http://www.editorandpublisher.com/feature/data-technology-and-digital-readers-are-shaping-how-the-printed-newspaper-looks-today/

By Gretchen A. Peck

If newspaper design had a motto, it might be: “Stick to the format. The design and layout is the brand.”

And that remains true today with iconic titles of newspapers rendered in familiar fonts and layouts that are distinctive in their own right. Think of how familiar and distinctive a title like USA Today is when you flip through the pages. The color, the layout, the way the headlines grab your attention—all part of the brand.

Newspaper publishers, by and large, have always understood this. But the notion that printed newspapers’ design should never deviate from the template is being challenged, and it’s because of digital and mobile publishing and the rising cost to paper. Still, that hasn’t stopped publishers from experimenting with their print product.

By Gretchen A. Peck

Efficiency is precisely why Dow Jones & Company, Inc. prints The Wall Street Journal at strategic points across the nation. The obvious benefit is that it “gets the Journal closer to our customers,” according to vice president of production Larry Hoffman. There was a time when the publisher operated its own printing plants — 17 back then — but today it relies more heavily on print suppliers, bringing the total number of sites printing The Wall Street Journal (and a mounting volume of commercial print) to 26, Hoffman said.

Read more at: https://www.editorandpublisher.com/feature/doing-more-with-less-in-the-pressroom/

Published by Editor & Publisher magazine, May 2014

By Gretchen A. Peck

Sticky graphics—that’s what print buyers want. Whether artists or marketers, they share a common goal to create images that grab attention and leave an impression, images that compel you, and perhaps even haunt you. Sometimes the vision calls for those images to become part of the environment, to be stuck on a wall, wrapped around architecture, placed over windows, and all kinds of surfaces.

It’s not unusual in large format graphics to print to interesting substrates that are both visually intriguing and install challenged. Specialty substrates—such as metallic and chalkboard—with adhesive applications abound, but print service suppliers must be both left- and right-brained when choosing among them. Print buyers look to the print provider for technical and performance guidance, as well as creative insight into how ideas may be achieved.

Read more at: http://www.digitaloutput.net/special-effects-sticky-images/

Published by Digital Output magazine, February 2014

By Gretchen A. Peck

There are a lot of variables throughout the print process. For example, the quality of the graphics, media choice, and the lighting and environmental conditions at the installation point. All of these factors contribute to the overall success of a print job. The same is true for how consumables and the print technology itself, including printheads, work together.

“Printheads are a crucial area of printer design, and what differentiates one printer manufacturer from another,” explains Mark Radogna, product manager, professional imaging, Epson.

Hardware manufacturers decide what type of printhead—piezo or thermal—to place in a device based on many factors. These include temperature and ink chemistry.

Read more at: http://www.digitaloutput.net/the-great-debate/

Published by Digital Output magazine, April 2014