50 States, 50 Fixes: How local climate solutions are resonating across America — my conversation with The New York Times’ Climate Editor Lyndsey Layton.

#NYTimes #climate #localnews

Writer. Editor. Photographer.

50 States, 50 Fixes: How local climate solutions are resonating across America — my conversation with The New York Times’ Climate Editor Lyndsey Layton.

#NYTimes #climate #localnews

“Any journalist will tell you. Sometimes you hear something so quotable that you can see the words in print in real time, right before your eyes. The room changes when deep truths are being spoken, when raw honesty is in the air.”—Cameron Crowe, “The Uncool: A Memoir”

If you’re a journalist who likes to see other journalists’ approach to the craft, I recommend Cameron Crowe’s autobiographical “The Uncool: A Memoir.” Crowe is a fascinating person. There is his undeniable storytelling talent, proven by his many decades as an accomplished music journalist, screenwriter and director.

There’s his encyclopedic knowledge of music from the 1960s-1980s — and perhaps beyond. There’s his almost Forrest Gump-like fortunes and happenstances, where he casually meets and vibes with so many important figures of those decades, from the worlds of music, industry, Hollywood. It’s a collage of pop culture.

The reader gets a sense of Crowe’s perspective on journalism, and the lessons he learned from mentors along the way. He wrestles with editorial dilemmas and relationships with sources. You sense the pressures he felt answering to editors, rock stars, publicists and readers — especially remarkable when he was a teenage reporter. That kid (then) had precisely what it takes to make a name, to build a byline and a brand: courage, resilience, introspection, fortitude, a great vocabulary, an inquisitive nature, and a little dash of naïveté.

The author says this is a story about family. Crowe’s family takes center stage throughout the book. Their connections are complicated, and he doesn’t sanitize them. He peels back the curtain on their shared tragedies and idiosyncrasies. It’s all relatable.

Naturally, in the memoir there’s the running theme of Crowe’s early life, which he so astutely, delicately captured in the semi-autobiographical film, “Almost Famous.” That is, his absolutely passionate love for music and reverence for the people who make it. You feel it. It’s almost tactile, vibrating off the printed page.

Chris Reen is Editor & Publisher (E&P) Magazine‘s Publisher of the Year.

Chris Reen is honored for his approachable optimism, reverence for journalism and a record of innovation, resilience and service to community.

Fourteen years ago, Nextdoor debuted on the digital networking scene. It carved out a niche as a website and app that facilitated connections between neighbors. It’s a digital space where they can share information, ask questions and seek recommendations relative to their geographic neighborhood.

This summer, Nextdoor unveiled a new design, returned to its original branding and logo, embraced local news — notably, at a time when other networking platforms devalue it — and incorporated Artificial Intelligence (AI) into the platform.

Read on at EditorAndPublisher.com:

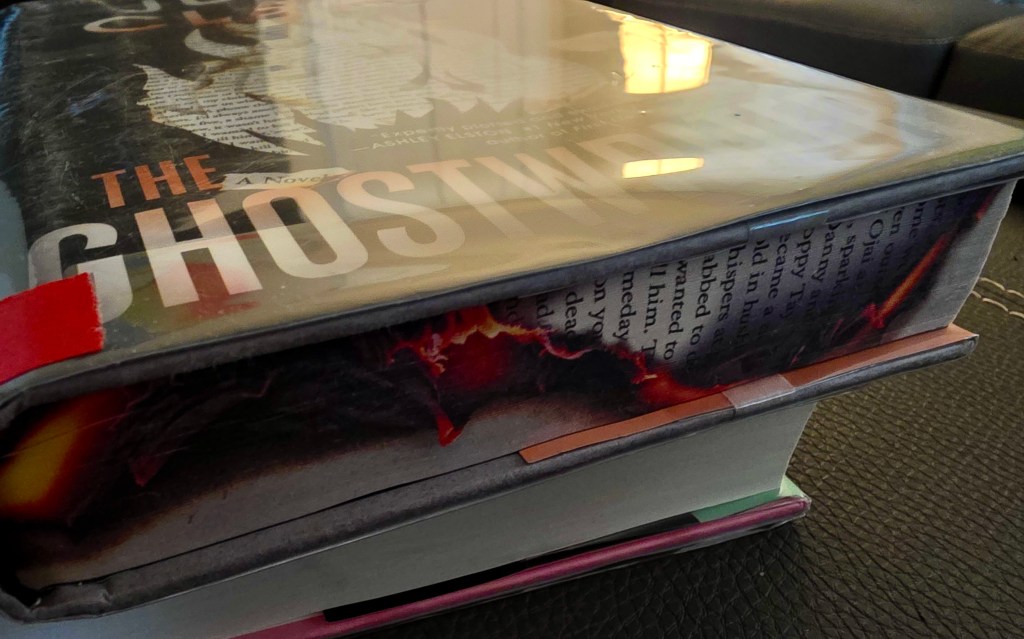

Love the printing on the book block’s trimmed edges. Grabbed my eye from the new-book shelves at the library. It’s “The Ghostwriter” by Julie Clark.

Some of the best Italian restaurants in Philadelphia are those you’ve never heard of. They have a small footprint, are intimate and cozy, with just a few tables. I’ve found that’s usually a good gauge of a great restaurant—symbolic that the focus is on quality rather than volume. They’re local-favorite spots, where families cook recipes passed down generations, and the vibe is spirited, familiar and comforting—like you’ve met up with some friends from the neighborhood to have a bottle of wine and some delicate handmade pasta ladled with Sunday gravy.

That type of culinary experience has eluded us since moving from Philadelphia more than a decade ago, until my husband and I discovered Paul’s Pasta Shop, right on the shore of the Thames River in Groton, Connecticut.

Though it was acquired by TyMark Restaurant Group in 2023, the restaurant still carries the name of its founder—Paul Fidrych. Partnered with his wife, Dorothy, Fidrych opened the restaurant in 1988, with a mission to deliver “fresh cooking and warm customer service.” Under the new ownership, the restaurant still makes good on that promise.

The dining room is tightly packed with green vinyl-covered tables, and there’s a covered deck out back, overlooking the Thames River. The menu is simple. They’re known for homemade pasta, simple green salads and a tempting dessert case. My husband tends to opt for the nightly specials, like linguini with shrimp, artichokes and sundried tomatoes. I tend to go for the house-made ravioli. You can order cheese or meat filling, or a few of each. It’s a great meal paired with a half-carafe of table wine, a basket of garlic bread and a simple house salad with the perfect amount of honey poppyseed dressing.

Their specialty is “spaghetti pie”—an enormous wedge of pasta, vegetables, cheese, sausage, pepperoni and sauce, baked in the oven until it develops a crust. I’m not brave enough to order it. It’s massive and requires a commitment. I’ve seen entire tables of Navy and Coast Guard service members order them and tap out halfway through. Makes for good leftovers, I bet.

The marinara sauce varies a little each time, but that’s how it goes in the kitchen, after all. Even precise recipes are subjected to variables, like the quality, season and sweetness of the tomatoes.

Is it the best marinara sauce I’ve ever had? No. But I’ve been spoiled on South Philly Italian; it’s an extremely high bar. But it’s a decent sauce; you’ll want to sop up any extra with the garlic bread.

The restaurant is approachable, unpretentious, homey. Locals wave to one another as they come through the front door. It’s particularly comforting to sit in the bustling dining room on a cold winter’s night, when you’re glad for the fellowship.

The staff is flawlessly friendly, and the service is quick. Pro tip: If you want cannoli for dessert, order them with your meal. They sell out fast.

Not long ago, we pulled off the highway and stopped in for dinner, and on our way out, we paused at the front of the store, where the manager, Mike, was making fresh pasta. We explained how we’d gotten into making pasta by hand at home, and he gave us some tips on dough and showed us how the commercial ravioli maker worked.

There’s limited parking behind the restaurant—right on the river, with views of the Gold Star Bridge, the State Pier, bustling with wind turbine industry, and the new Coast Guard Museum under construction in New London.

As we strolled to our car one night after a fair-valued perfectly satisfying meal, my husband declared, “It’s the closest thing to South Philly.” That’s a high compliment.

QUICK READ: How top journalists protect sources and turn secrets into stories

Read at the link or in the September 2025 Editor & Publisher print edition:

“This is an area where more boards of directors than ever are looking for continued updates, not just on the state of the law and the state of enforcement policy, but what it all means in terms of their own companies’ practices. … This is complicated stuff.” — Camille Olson, partner, Seyfarth Shaw LLP

E&P’s August 2025 Cover Story: Experts weigh in on how DEI can survive and evolve in today’s volatile media and legal landscape

https://www.editorandpublisher.com/stories/whats-next-for-dei-in-newsrooms,257042

Quick Read: The Houston Chronicle investigative team—double the size it was just a year ago—digs deep into the questions that matter most to Houstonians